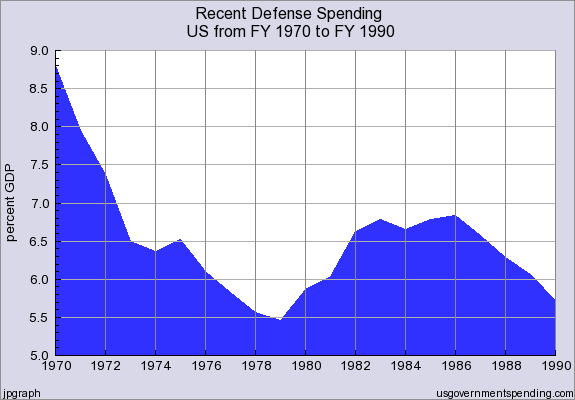

The Atlantic wrote a classic article on David Stockman, the Director of the Office of Management and Budget, during the early years of the Reagan administration. I recommend the article to anyone who has too much time on their hands: The Education of David Stockman. If you stop to think for a moment what difficulties the Director of the OMB would face in Washington during the Reagan years. It looks like this:

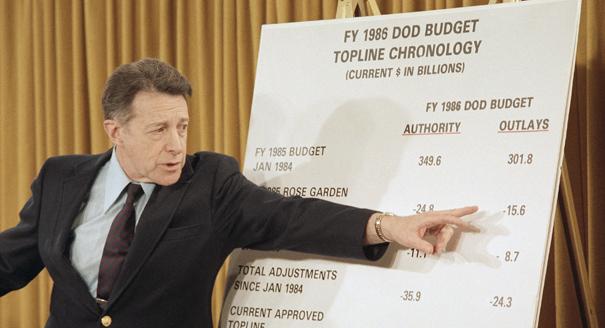

In other words, “John Anderson, running as an independent candidate for President in 1980, had asked the right question: How is it possible to raise defense spending, cut income taxes, and balance the budget, all at the same time?” This from Stockman’s mentor. “The Education of David Stockman”—written in 1981—doesn’t confront you with the fact that Stockman had hit a wall balancing the budget on day one due to the colossal ambitions of Secretary of Defense, Caspar Weinberger who was chummy with the President. It merely hints at this. Quite possibly, Stockman wanted to keep his job and had to repress a litany of complaints about Weinberger. Weinberger, as I’ve posted about once or twice on facebook truly steamrolled him at meetings. Here:

As Stockman watched in shock, Weinberger also presented a blow-up cartoon in the form of a poster depicting three soldiers. One was a pygmy who carried no rifle. He represented the Carter budget. The second was a four-eyed wimp who looked like Woody Allen, carrying a tiny rifle. That was Stockman’s budget. Finally there was ‘GI Joe himself, 190 pounds of fighting man, all decked out in helmet and flak jacket and pointing an M-60 machine gun. This imposing warrior represented, yes, the Department of Defense budget.’

Stockman was well aware Weinberger didn’t come out of the woodwork (he was educated at Harvard.) He later referred to these tactics as “Sesame Street” in amazement.

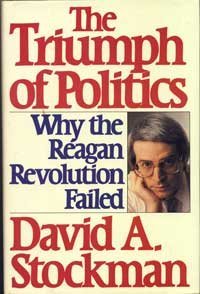

What makes this all the more tragic is that Stockman was a true believer in a vision of very limited government: “Stockman hoped to create a ‘minimalist government… a spare and stingy creature which offered even-handed public justice but no more.” A disillusioned Stockman would later cry that Reagan had “no blueprint for radical government.” Indeed, he’d write a book on the subject:

Although, Stockman was associated with the supply-side movement, he was not fooled by the infamous Laffer Curve which suggests you can actually raise more tax revenue by cutting taxes (?!):

The original apostles of supply-side, particularly Representative Jack Kemp, of New York, and the economist Arthur B. Laffer, dismissed budget-cutting as inconsequential to the economic problems, but Stockman was trying to fuse new theory and old. “Laffer sold us a bill of goods,” he said, then corrected his words: “Laffer wasn’t wrong—he didn’t go far enough.

“The hard part of the supply-side tax cut is dropping the top rate from 70 to 50 percent—the rest of it is a secondary matter,” Stockman explained. “The original argument was that the top bracket was too high, and that’s having the most devastating effect on the economy. Then, the general argument was that, in order to make this palatable as a political matter, you had to bring down all the brackets. But, I mean, Kemp-Roth was always a Trojan horse to bring down the top rate.”

In effect, Stockman agreed with Keynesian critics of supply-side economics on what the essence of the movement was about: “the supply-side theory was not a new economic theory at all but only new language and argument to conceal a hoary old Republican doctrine: give the tax cuts to the top brackets, the wealthiest individuals and largest enterprises, and let the good effects “trickle down” through the economy to reach everyone else.” Stockman himself said “It’s kind of hard to sell ‘trickle down,'” he explained, “so the supply-side formula was the only way to get a tax policy that was really ‘trickle down.’ Supply-side is ‘trickle-down’ theory.” Stockman genuinely believed in tax cuts to stimulate investment, but he could not accept across the board cuts that would endanger his beloved budget. He offers an odd window into the thinking of less altruistic conservatives in the 1980s. There is a valid question of why he’s revealing all of this to a journalist, while he’s in office. I think simply put, he correctly recognized he was on a crusade and wanted to safeguard himself against failure. Another thing to keep in mind, is that this guy used to be a bonafide Marxist in his youth. When he started taking political science classes from Neo-Conservatives he said he discovered “that it was possible to have a sophisticated view of the world without being a Marxist.” ! The sweet siren song of Marxism for young David. I can imagine Stockman laboring over Das Kapital thinking he had unlocked the workings of history. Just listen to the man speak fervently on his later conservative faith:

This was the core of his complaint against the modern liberalism launched by Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal. He did not quarrel with the need for basic social-welfare programs, such as unemployment insurance or Social Security; he agreed that the government must regulate private enterprise to protect general health and safety. But liberal politics in its later stages had lost the ability to judge claims, and so yielded to all of them, Stockman thought, creating what he describes as “constituency-based choice-making,” which could no longer address larger national interests, including fiscal control. As Stockman saw it, this process did not ameliorate social inequities; it created new ones by yielding to powerful interest groups at the expense of everyone else. ‘What happens is the politicization of the society. All decisions flow to the center. Once we decide to allocate credit to certain activities—and we’re doing that on a massive scale—or to allocate the capital for energy development, the levels of competency and morality fall. Then the outcomes in society begin to look more and more like the work of brute muscle. The other thing it does is destroy ideas. Once things are allocated by political muscle, by regional claims, there are no longer idea-based agendas.”

I certainly can’t understand all of this vision for disinterested government. And Stockman certainly cannot understand Reagan. Reagan explained the position of his administration to his cabinet as “defense is not a budget item.” The charade Stockman was asked to take part in was finding a way to balance the budget, which Reagan committed to, without touching defense whatsoever. The process was agonizing, yet Stockman maintained optimism for some time:

No President had balanced the budget in the past twelve years. Still, Stockman thought it could be done, by 1984, if the Reagan Administration adhered to the principle of equity, cutting weak claims, not merely weak clients, and if it shocked the system sufficiently to create a new political climate. He still believed that it was not a question of numbers. “It boils down to a political question, not of budget policy or economic policy, but whether we can change the habits of the political system.”

Changing the habits of the political system was going to entail going after Social Security and so called “health costs” Medicare and Medicaid. That’s very ambitious David. The ironic thing is that he actually tried this: “Stockman carried with him a big black binder enclosing a “Current Services Budget,” which listed every federal program and its current cost projections. He hoped to memorize the names of 500 to 1,000 program titles and major accounts by the time he was sworn in—an objective that seemed reasonable to him, since he already knew many of the budget details.” This was an intensely committed guy. He even opposed a Chrysler bailout, when he was just a representative from Michigan. “Stockman was the only Michigan representative to oppose it, even though a large town in his district, St. Joseph, would be hurt. The town’s largest employer, St. Joe’s Auto Specialties, was a Chrysler supplier, and its factory was laying off workers. Its owners were among Stockman’s earliest and largest contributors when he first ran for Congress, in 1976.” He just might have been on to something, when he said, “Some of them were a little miffed at me and others applauded. I only had one or two argue strenuously with me. They’re probably more derogatory behind my back.” He brought this ideological consistency—or fundamentalism—with him to Washington. Just to get more than a vague sense of the Sisyphean task he was dealt, here’s a lucid explanation of the problem:

Reagan had campaigned on the vague and painless theme that eliminating “waste, fraud, and mismanagement” would be sufficient to balance the accounts. Now, as Stockman put it, “the idea is to try to get beyond the waste, fraud, and mismanagement modality and begin to confront the real dimensions of budget reduction.” the new administration would have to go for a budget reduction in the neighborhood of $40 billion. “Do you have any idea what $40 billion means?” he said. “It means I’ve got to cut the highway program. It means I’ve got to cut milk-price supports. And Social Security student benefits. And education and student loans. And manpower training and housing. It means I’ve got to shut down the synfuels program and a lot of other programs. The idea is to show the magnitude of the budget deficit and some suggestion of the political problems.”

It turned out not only was defense off limits, but Reagan decided there would be no touching the “social safety net” because it was political poison. The social safety net was comprised of the “main benefit programs of Social Security, Medicare, veterans’ checks, railroad retirement pensions, welfare for the disabled.” Stockman came into office with a vision he felt would appeal across the aisle: “We are interested in curtailing weak claims rather than weak clients,” he promised. Now he was finding himself in a position to create no meaningful legacy and could only moan to The Atlantic interviewer William Greider: “‘Do you realize the greed that came to the forefront?’ Stockman asked with wonder. ‘The hogs were really feeding. The greed level, the level of opportunism, just got out of control.'” He then spoke of a new awareness of the defense budget:

“I put together a list of twenty social programs that have to be zeroed out completely, like Job Corps, Head Start, women and children’s feeding programs, on and on. And another twenty-five that have to be cut by 50 percent: general revenue sharing, CETA manpower training, etcetera, etcetera. And then huge bites that would have to be taken out of Social Security. I mean really fierce, blood-and-guts stuff—widows’ benefits and orphans’ benefits, things like that. And still it didn’t add up to $40 billion. So that sort of created a new awareness of the defense budget.

Here’s Stockman trying to sell congress on taking away orphan’s benefits, while Cap Weinberger is presiding over the biggest peace time increase in the defense budget in U.S. history. By the end of the article he’s become so vexed it’s disturbing.

Does anyone truly understand, much less control, the dynamics of the federal budget intertwined with the mysteries of the national economy? Stockman pondered this question occasionally, but since there was no obvious remedy, no intellectual construct available that would make sense of this anarchical universe, he was compelled to shrug at the mystery and move ahead. “l’m beginning to believe that history is a lot shakier than I ever thought it was,” he said, in a reflective moment. “In other words, I think there are more random elements, less determinism and more discretion, in the course of history than I ever believed before. Because I can see it.”

Yes David, you can see it. “The Republican Robespierre” had become central casting for an ineffectual bureaucrat. A real turning point came, when Reagan sat down in front of television for a fireside chat. This had been the moment Stockman was waiting for. Only it took the form of disowning his reform plan. “Reagan said that there was a lot of “misinformation” about in the land, to the effect that the President wanted to cut Social Security. Not true, he declared, though Reagan had proposed such a cut in May.” Of course, there were last gasps from Stockman: “Defense is setting itself up for a big fall,” Stockman had predicted. “If they try to roll me and win, they’re going to have a huge problem in Congress. The pain level is going to be too high. If the Pentagon isn’t careful, they are going to turn it into a priorities debate in an election year.” THE PAIN LEVEL IS GOING TO BE TOO HIGH. And, of course, “The 1982 election cycle will tell us all we need to know about whether the democratic society wants fiscal control in the federal government,” Stockman said grimly. Democratic society did not care. Ironically enough, some have argued “massive federal expenditures for defense” was more of a factor than market forces in the Reagan Recovery Stockman was obsessed with designing. The way to access Reagan was human interest stories and anecdotes far more than facts and figures, but even if Stockman busted out the old locker room humor it’s doubtful he would have had a chance. When people talk about small government, they most likely are not thinking of Stockman’s Honey I Shrunk The Kids state. Those that that are thinking of that are mostly confined to internet forums.

And Now, The Wall of Stockman:

Sources: